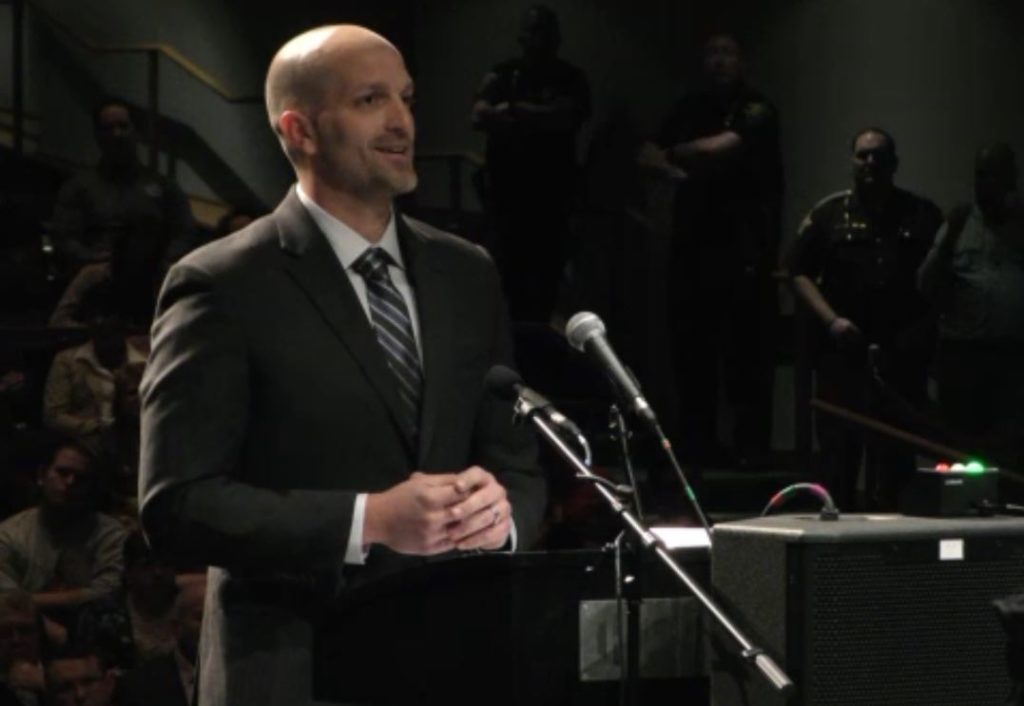

Webster & Garino At Indiana’s Supreme Court

On April 18, 2019, William Webster of Webster & Garino argued the Indiana cell phone case before the Supreme Court of Indiana. The case, Katelin Eunjoo Seo v. State of Indiana, Trial Court Cause No. 29D01–1708–MC–5640, and Appellate Court Case Number 18S-CR-595, went up on appeal to the Supreme Court after the Court of Appeals of Indiana ruled in favor of Mr. Webster’s client, criminal defendant, Ms. Seo.

The issue addressed in this Appeal is whether the government can compel a criminal defendant to unlock a cell phone through her recollection and use of a memorized password or whether this violates the United States Constitutional Fifth Amendment and Indiana Constitutional privilege against self-incrimination.

Background

The attorneys at Webster & Garino contend that compelling a criminal defendant to provide a password to her cell phone does, indeed, violate a defendant’s rights against self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution and Article 1, Section 14 of the Indiana Constitution.

The facts involve charges against Ms. Seo for alleged stalking, intimidation, harassment, and theft. Subsequently, the State of Indiana filed thirteen counts of invasion of privacy against Ms. Seo.

The State of Indiana conceded that it is seeking to obtain the contents of Ms. Seo’s cell phone to search for incriminating evidence against her in the pending criminal cases, as well as other criminal investigations.

The Trial Court issued an Order finding that the “act of unlocking the phone does not rise to the level of testimonial self-incrimination that is protected by the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution or by Article 1, Section 14 of the Indiana Constitution.” The Trial Court found Ms. Seo to be in contempt of court because she would not provide her password and ordered her to jail indefinitely until she provided her password to law enforcement.

Webster & Garino filed a Motion to Stay the Contempt Finding Pending Appeal in the Indiana cell phone case. The Trial Court granted the Motion to Stay pending an Appeal. The State of Indiana then filed additional criminal charges against Ms. Seo. Ms. Seo filed a Notice of Appeal.

The Court of Appeals agreed with Webster & Garino’s position and reversed the Opinion of the Trial Court. The State of Indiana thereafter appealed this matter to the Indiana Supreme Court. William Webster argued the issue before the Supreme Court in Katelin Seo v. State of Indiana, 18S-CR-595, on April 18, 2019.

Legal Arguments

It is the position of Webster & Garino that providing a password is a testimonial communication. Both the United States Constitution and the State of Indiana Constitution provide protection against self-incrimination. Specifically, the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides that “No person shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself,” and Article 1, Section 14 of the Indiana Constitution states “No person in any criminal prosecution shall be compelled to testify against himself.” See U.S. Const. Am. 5; IN Const. Art. 1, Sec. 14.

This guarantee against testimonial compulsion, like other provisions of the Bill of Rights, “was added to the original Constitution in the conviction that too high a price may be paid even for the unhampered enforcement of the criminal law and that, in its attainment, other social objects of a free society should not be sacrificed.” See Feldman v. United States, 322, U. S. 487, 489 (1944). This provision of the Amendment must be accorded liberal construction in favor of the right it was intended to secure. See Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.S. 547, 562 (1892); Arndstein v. McCarthy, 254 U.S. 71, 72-73 (1920).

In determining whether Ms. Seo is permitted to invoke her constitutional privilege in response to a Court-Ordered search warrant compelling Ms. Seo to provide her password to unlock her cell phone, the Court must determine if requiring Ms. Seo to provide her password is testimonial and incriminating.

In Doe v. United States, 487 US 201, 212, 108 S. Ct. 2341, 101 L. Ed. 2d 184 (1987), the Supreme Court found: “An act is a testimonial when the accused is forced to reveal his knowledge of facts relating him to the offense or from having to share his thoughts and beliefs with the government.” In Doe, the Court found that a court order compelling the defendant to sign a consent to authorize foreign banks to disclose records of his accounts did not violate his privilege against self-incrimination. See id., at 202. However, the Court made this significant distinction which would be applicable here: “We do not disagree with the dissent that expression of contents of individual’s mind is testimonial communication for purposes of the Fifth Amendment. We simply disagree with the dissent’s conclusion that the execution of the consent directive at issue here forced petitioner to express the contents of his mind. In our view, such compulsion is more like being forced to surrender a key to a strongbox containing incriminating evidence that it is like being compelled to reveal the combination to petitioner’s wall safe.” See id., at 210, fn. 9 (emphasis added). The Court in Doe further stated that “it is the extortion of information from the accused, the attempt to force him to disclose the contents of his own mind that implicates the Self-Incrimination Clause.” See id., at 211 (emphasis added).

As Webster & Garino argued, in this case, Ms. Seo is not being compelled to sign a consent form to obtain phone records from a third-party. Instead, the State of Indiana is seeking the contents of Ms. Seo’s mind to compel her to provide knowledge of her password to assist the State in searching her phone for incriminating evidence. The State of Indiana intends to use this evidence against Ms. Seo in not only her pending criminal cases but also in her pending criminal investigations.

If just the assembly of documents was found by the U.S. Supreme Court to be in violation of a defendant’s privilege against self-incrimination, then, as Webster & Garino argued, surely requiring Ms. Seo to provide her password to the State of Indiana to assist in the prosecution of her own criminal cases violates Ms. Seo’s rights against self-incrimination. There is no dispute in this matter that the State of Indiana is seeking to obtain Ms. Seo’s password to search her phone for incriminating evidence. This is the very “link in the chain” identified and prohibited in Hoffman.

The State argued that providing her password is not testimonial as the State is not seeking Seo to provide her password only to unlock her phone, arguing that Seo could unlock her phone without ever informing law enforcement of her password. However, by unlocking her phone Seo is communicating that the contents of her phone (which include text messages, emails, pictures, calendars, videos, all her movements with geo-positioning and a multitude of additional information) exists, are under her control and authentic. Webster and Garino argued that the communicative aspects of unlocking the phone, as provide above, are testimonial and protected under the 5th Amendment.

The State of Indiana argued in the Indiana cell phone case that even if Ms. Seo’s password is a testimonial, it is not protected under the 5th Amendment if it is a “foregone conclusion” that Ms. Seo has access and control over the phone at issue. In support of this argument, the State relied on Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391 (1976), in which the Court found that requiring a client’s attorneys to provide documentation prepared by the client’s accountants did not violate the client’s Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. The Court reasoned: “Surely the Government is in no way relying on the truth-telling of the taxpayer to prove the existence of or his access to the documents. The existence and location of the papers are a foregone conclusion, and the taxpayer adds little or nothing to the total of the Government’s information by conceding that he, in fact, has the papers.” See id., at 421.

However, the facts are not analogous to Fisher. In Fisher, the client’s accountant prepared documents, which was sent to the client and then later forwarded to the client’s attorney. The Court reasoned that the existence of the documents was a foregone conclusion and that their existence did not rely on any statements made by the petitioners. In contrast, in this matter, there is no foregone conclusion that anything exists on Ms. Seo’s phone. The State of Indiana is relying on statements made by Ms. Seo as they are attempting to compel her to provide the password to her phone.

Webster and Garino argued that the foregone conclusion doctrine has never been applied by the US Supreme Court to testimony only documents in possession of 3rd parties. Webster and Garino further argued that if Seo’s password was a foregone conclusion, then the State would already know her password.

In addition to the arguments set forth above, it is the position of Webster & Garino that the State of Indiana presented primarily policy arguments, assumptions and hypotheticals that suggested that if the Indiana Supreme Court affirms the decision of the Indiana Court of Appeals, States will be incapable of executing search warrants and obtaining evidence, a new zone of lawlessness will be created where child pornographers and drug dealers can operate without fear of law enforcement, and the public will want and encourage lawmakers to pass new draconian anti-privacy legislation.

Even though encryption is relatively new in our society, the frustration articulated by the States is not: investigators believe additional evidence of a crime exists and the person investigators believe has the knowledge necessary to obtain that evidence is the criminal suspect. Decades if not centuries of precedent and practice support the conclusion that a suspect cannot be compelled to recall and use information that exists only in his or her mind to aid the government’s prosecution. See Curcio v. United States, 354 US 118, 128 (1957). Absent a grant of immunity, that compulsion violates the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

Counsel recognizes the challenges law enforcement agencies face in criminal investigations and the vital role they play in our society. However, the Fifth Amendment should not be viewed as an inconvenience to law enforcement. The Court’s focus should be on the zone of liberty the Fifth Amendment affords — not the hypothetical zone of lawlessness the States propose the Fifth Amendment creates. This guarantee against testimonial compulsion, like other provisions of the Bill of Rights, “was added to the original Constitution in the conviction that too high a price may be paid even for the unhampered enforcement of the criminal law and that, in its attainment, other social objects of a free society should not be sacrificed.” See Feldman v. United States, 322, U. S. 487, 489 (1944). This provision of the Amendment must be accorded liberal construction in favor of the right it was intended to secure. See Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.S. 547, 562 (1892); Arndstein v. McCarthy, 254 U.S. 71, 72-73 (1920).

The State of Indiana also framed the term and use of “encryption” as something secretive or concealing, suggesting that someone who uses encryption does so for the nefarious purpose of concealing the true meaning of a message. The States went so far as pointing out that the word encryption is based in part from the Greek word meaning “secret writing.” See Brief of Amici Curiae State of Utah et al, p. 7-8. The States suggested that it is “essentially impossible for even the most powerful computers to break a digital lock by current brute force techniques that try every combination.” Id. p. 10.

In reviewing the State’s explanation of encryption, one could come to the opinion that encryption is a tool only reserved for criminal enterprises. Further, in making their argument, the State relied on articles written by Orin S. Kerr, who is a former federal computer crimes investigator. However, encryption is integral for safeguarding the privacy and security of sensitive, electronically stored information. The use of encryption is now routine practice for individuals and businesses. Computer and software manufacturers consider disk encryption a basic security measure, and it is a standard feature on most new computers. Device encryption is also a standard feature for the leading smartphone operating systems, Apple IOS and Android. In addition, government agencies recommend encryption to protect personal information. As Webster & Garino argued, in our increasingly connected world where we share and transmit information, encryption is an important integral part of modern life.

Even though encryption offers presumably millions of people the benefit of safeguarding private information, despite the State’s contention, encryption is not unbreakable. The government can use a variety of techniques to gain lawful access to encrypted information without compelling the aid of a criminal suspect. For example, law enforcement could circumvent many forms of encryption by using software or hardware that exploit flaws in the encryption program or the device itself. To illustrate, investigators were able to break the encryption on an iPhone used by the perpetrator of the San Bernardino terrorist attack. Some reports have suggested that law enforcement agencies have contracted with companies and purchased tools to bypass encryption. Further, law enforcement could obtain a warrant to install a camera to record a suspect’s keystrokes or install software called “keylogger” that captures the characters typed using the device. The above methods, for example, would provide law enforcement with the password without compelling the criminal suspect to provide his or her password.

One final argument presented by the State in the Indiana cell phone case is that “the Indiana Court of Appeals’ Opinion’s holding drastically alters the balance of power between investigators and criminals and renders law enforcement often incapable of lawfully accessing relevant information.” Id. p.11. However, Webster & Garino argued that encryption does not drastically alter the balance of power. In fact, in Ms. Seo’s case, prosecutors were able to obtain additional evidence from other parties, which resulted in Ms. Seo pleading guilty to all her criminal cases, without the need of compelling her to provide the password to her phone.

As indicated above, encryption protects essential and intimate details of our lives. Technology creates long-lasting records of photos, voice recordings, videos, text messages, emails, calendars, internet searches, and other various documents and files. Further, our mobile devices create logs of where we have been, who we are with, and where we are going. See United States v. Jones, 565 US 400, 415 (2012) (“GPS monitoring generates a precise, comprehensive record of a person’s public movements that reflects a wealth of detail about her familial, political, professional, religious and sexual associations.”). Encryption is designed to help to protect the above information in the modern world. As the Eleventh Circuit stated, encryption is not merely a tool for criminals. Cf. Doe II, 670 F.3d at 1347 (“Just as a vault is capable of storing mountains of incriminating documents, that alone does not mean that it contains incriminating documents, or anything at all.”).

The Supreme Court has not yet issued a decision on the cell phone case in Indiana. The Opinion will have significant implications for the citizens of Indiana. Courts and lawmakers around the country are also likely awaiting a decision as there is little direct case law on this issue given the rapidly-evolving changes in technology. Numerous states, including Utah, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania, joined to a filed Amicus Brief before the Supreme Court – presenting arguments in support of the State of Indiana. The ACLU also filed an Amicus Brief before the Indiana Supreme Court in support of Ms. Seo’s position, which can be viewed here.

Webster & Garino has been contacted by attorneys and law schools across the nation to discuss this matter for the Indiana cell phone case.

LIST OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Arndstein v. McCarthy, 254 U.S. 71 (1920)

Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.S. 547 (1892)

Curico v. United States, 354 U.S. 118 (1957)

Doe v. United States, 487 U.S. 201 (1988)

Feldman v. United States, 322, U. S. 487, 489 (1944)

Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391 (1976)

Hoffman v. United States, 341 U.S. 479 (1951)

In Re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum, 670 F.3d 1335 (11th Circuit 2012)

United States v. Hubbell, 530 U.S. 27 (2000)

United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400 (2012)

Watkins v. State, 85 N.E.3d 597 (Ind. 2017)

Constitutional Provisions

Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution

Article 1, Section 14 of the Indiana Constitution

Statute

Ind. Code § 35-33-5-11 (West 2016)

Read on: How to calculate child support for self employed people